Black hair is a language with many dialects. It is diverse in texture, curl patterns and styling, and speaks of ethnic markers, social standing, histories, joys, and complexities. But it is also a language that can be misunderstood and misinterpreted. Sometimes we, who own it, struggle to understand it. Some of us are tongue-tied as we placate a gaze not of our own choosing, in a system not of our own making.

But today, Black women are discovering ways of speaking their ‘hair truths’, by going natural, learning how to properly maintain chemically straightened hair, going for the ‘big chop’, trying out locs and plant-based extensions. Veiled Black Muslim women who have curlier hair patterns (see chart below) arguably hold unique perspectives into the relationship between the feminine, spirituality, and hair. One of these relates to the current natural hair movement, which like the Black Is Beautiful movement of the 1960s and 1970s, encourages women of African descent to celebrate the ‘natural characteristics’ of their hair.

The 2010s spawned the rise of the YouTube influencer and subsequently hair tutorials and natural hair diaries, which heavily influenced my decision to go natural in 2013. But I also felt Black Muslim women were being left out of the conversation. So, over five years ago, I penned a piece in the Huffington Post called, ‘Are Black Muslim Women Part Of The Natural Hair Conversation?’ It was picked as one of the platform’s top ten blogs in 2016.

While the hijabis no longer unheard of in the fashion industry – thanks to Black Muslim models and designers like Halima Aden, Ayana Ife, and Nailah Lymus – discussions around hair involving Black Muslim women are slow in taking off. And this is not without precedent.

Hair narratives for Black Muslim women reflect the struggle to be considered ‘normal’ in the communities that Black Muslims generally intersect. For instance, it could be argued that the wearing of the hijab may create the impression that ‘Black hair struggles and joys’ are not applicable to Black Muslim women. An example of this is the tussle that Black women have had in places of work, where their hair and traditional styles are in some instances seen as unprofessional. If a Black Muslim woman wears the hijab, that struggle is automatically replaced with the struggle for hijab to be accepted. On the other hand, discussions on hijab and hair within the wider Muslim community tend to leave out the distinct experiences of Black Muslim women.

Despite these difficulties, Black Muslim women are developing their own ‘hair hermeneutics’. This is happening at a time that historian and anti-racist activist, Ibram X. Kendi describes as the ‘Black Cultural Renaissance’, where Black people are ‘shedding what and who do not serve us’. The manifestations of this include better representations of Black people across the arts, culture, politics, and music, and greater efforts at self-determination. We see a greater presence of Black film biopics (Selma, Harriet Tubman), documentaries and series (13th, Small Axe), Black award shows (Black Girls Rock, the MOBO awards), the creation of Black economic strategies such as the ‘Black Pound’, diaspora initiatives such as Ghana’s 2019 Year of Return initiative and the first African Union-CARICOM summit in Autumn 2021. Then there are recent music albums that amplify Black empowerment such as Kendrick Lamar’s ‘To Pimp a Butterfly’, Beyoncé’s ‘Black is King’, and Nas’s ‘King’s Disease II.’

Besides the 2019 Oscar-winning animated film ‘Hair Love’, by athlete-turned filmmaker Matthew A. Cherry and other similar films and shows, nowhere has the subject of Black hair been more prominently approached than through song in recent times. India Arie’s 2006 neo-soul classic ‘I Am Not My Hair’ and Solange Knowles’s 2016 beauty anthem ‘Don’t Touch My Hair’ pretty much mean what they say. These two songs also reflect different hair dialects that I believe exemplify Black Muslim women’s narratives, and which incorporate their cultural and spiritual ties, that is to say: ‘I am more than my hair, but my hair matters to me.’

I propose that ‘Can’t Touch My Hair’might be another suitable mantra for Black Muslim women, when one considers how the veil and the hijab relate to hair in Islam.

Dalilah Baruti’s How to Look After Your Natural Hair in Hijab explores ‘healthy’ hair and the spiritual root of Black hair language for Muslim women. Not all cover their hair, but for those who do, the hijab is in conformity with Islam’s sacred scriptures. As the Qur’an says:

And say to the believing women that they should lower their gaze and guard their modesty; that they should not display their beauty and ornaments except what must ordinarily appear thereof; that they should draw their veils over their bosoms…And O you Believers, turn you all together towards Allah, that you may attain Bliss (24:31).

Baruti does not suggest verses like this specifically refer to Black hair, but she does draw upon the honour that Allah in the Qur’an confers upon the diverse phenotypic traits inherent in all of humankind: ‘We have indeed created mankind in the best of moulds’ (95:4). The celebration of the distinctive qualities and traits within the human race are also supported by: ‘O mankind, indeed We (Allah) have created you from male and female and made you peoples and tribes that you may know one another’ (49:13). The Prophet Muhammad is quoted as saying, ‘Whoever has hair, should honour it’ (Sunan Abi Dawud, Hadith 4163).

Black Muslim women have to take into account hairstyles that fit their Islamic lifestyle, which distinguishes them from both non-Black Muslim women and Black non-Muslim women. For instance, while protective styles such as wigs, weaves and extensions (both natural and synthetic) are primarily (but not solely) worn by some Black women, Black Muslim women’s access to these are subject to debate among some scholars of Islamic jurisprudence. As Cambridge Special Livingstone PhD scholar, Michael Mumisa explains to me, jurists or fuqaha from some schools of thought are opposed to hair extensions of all types because of their reading of a hadith from the Prophet Muhmmad, that prohibits the use of human hair. On the other hand, jurists from the Hanafi school of thought allow the use of synthetic hair extensions. Muslim hair blogger, RaySunshine tells me that some non-Black scholars are becoming more expedient on matters relating to Black hairstyles. She mentions Assim Al-Hakeem, who in 2019, slightly changed his cautious fatwa on the permissibility of locs. They are associated with followers of Rastafari which forbids the cutting of hair. But locs are also worn by other Black women and men as a protective style,therefore Islamic rulings on such matters overridingly affect Black Muslims.

The hijab is often regarded as more than just a ‘headscarf’ by Muslim scholars, and yet the relationship between Black Muslim women and ‘head coverings’ is part of a wider story of what covering means for different women of the African diaspora. Among some ethnic groups, the headwrap is considered an extension of the hair and can appear as a short, patterned turban that covers the ears or a long flowing scarf that extends all the way to a woman’s back. In Veiled Self, Transparent Meanings: Tuareg headdress as a social expression, Susan Rasmussen shows veils and scarfs can have distinct social and cultural meanings among Muslim groups in African contexts. In the case of the Tuareg ethnic group, the veil can be used for ornamental and flirtatious purposes for both men and women. And it is considered a sign of elegance which is why young women may take up the veil before menstruation or marriage.

Along the Gulf of Guinea, head wrappings tend to have a more ceremonial purpose rather than a diurnal one. This is particularly inextricably linked to the Black immigrant experience in the West where headwraps are, generally, worn during special occasions. For instance, among Nigerian Yoruba people and ethnic groups in Sierra Leone, geles or enkeychas are worn during weddings, Eid, baby naming ceremonies known as Aqiqahs, and baptism. In Ghana, dukus are worn on religious days by Muslims, Seventh-Day Adventists, or Sunday church-going Christians.

‘Mother of the South African nation’ and former apartheid activist Winnie Madikizela-Mandela is credited for reviving the doek, which was imposed on Black women to ‘control’ their exoctism from white men in South Africa, according to Professor Hlonipha Mokoena of the Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research. She famously wore one to court to protest her husband, Nelson Mandela, being put on trial for leaving the country without a valid passport in 1962. She continued to wear the doek, inspiring others to embrace their cultural heritage. When she died, #AllBlackWithADoek trended on Twitter, showing South African women donning it in her honour. Likewise, a number of high profile continental African women have been pictured in headscarves, such as Tanzania’s first female president Samia Suluhu Hassan, former Liberian president Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf , former Malawian president Joyce Banda and former African Union head Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma.

In the larger Black Atlantic diaspora, head coverings came to represent European colonial domination over enslaved populations. When enslaved Africans stepped off the slave ship in the New World, hairstyles and coverings that represented their various ethnicities, lineages, languages, religion and marital status were shaved or stripped off, thereby symbolising the cultural and physical uprooting that was intrinsic to the chattel slave experience. Essence’s 2020 ‘Respect Our Roots’ article details the psychological and mental trauma that enslaved African women would have experienced, and how hair came to reflect their struggle for survival:

Before the captured boarded the slave ships, traffickers shaved the heads of the women in a brutal attempt to strip them of their humanity and culture. Perhaps colonisers recognised the significance of the elaborate strands. In any case, they sought to take away the women’s lifeline to their homeland. As the women endured the rigors of slavery in America, braids became more functional…. [So] braiding becomes a practical thing… [Hairstyles needed to] last an entire week.

The overarching degradation of enslaved peoples was codified in a series of laws that set the stage for the appalling race relations that are central to the story of the United States.

During the eighteenth century, enslaved Africans in South Carolina were required by the 1735 Negro Act to cover their hair in head rags to accommodate the harsh demands of field work.

And in New Orleans, the 1786 Tignon laws required free Creole women to wear a tignon or scarf to signify they were members of the slave class, irrespective of whether they were actually free or not.

Imani Bashir, a Black American Muslim and travel writer based in Mexico, says that there has always been a distinctive relationship between head covering, Blackness, and faith in the US. ‘I honestly believe hijabhas an ancestral component that a lot of people don’t know and don’t realise. As somebody who comes from multi-generations of Black Muslims in the US, there is a history of Black Muslims who kept their deen (religion) by covering themselves, covering their hair, fasting during the month of Ramadan and during slavery. There’s just a lot of intermingling of what it is to be Black, what it is to be Muslim, and what it is to be a woman.’

‘The radical history of the headwrap’, on the website Timeline, details how the Black Power movement and subsequently, conscious hip-hop artists like Queen Latifah during the 1980s and 1990s, would take back ownership and make the head wrap a powerful symbol of autonomy, with a nod to African heritage and Black pride. But in the United States, that sense of pride began much earlier in the twentieth century with the onset of the Nation of Islam (NOI). The movement played a vital role in rearticulating the feminine, spiritualism, and veiling that propelled the image of its female followers as a core representation of the movement’s ideals and purpose. Women of the NOI are renowned for their distinctive form of hijab that comprises long white or other coloured gowns, and a head covering that may show the neck and flows behind the head, as opposed to the front of the neck and bosom, normally worn by Muslim women in mainstream Islam.

In Women of the Nation: Between Black Protest and Sunni Islam, former NOI member Shirley Morton says that the movement empowered her to embrace her ‘natural beauty.’ ‘I am happy and proud to be Black… I know that I am the mother of civilisation. I wear the clothes of civilised people. My dresses are far below my knees and I love it… The honourable Elijah Muhammad teaches us that we Black women are the most beautiful of all women.’

Kayla Renée Wheeler, an Assistant Professor of Gender and Diversity at Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio, argues that Black Muslim fashion started in the United States in the 1930s. It was intrinsic to challenging both white supremacist beauty standards and Arab-centrism, and helped propel the creation of an Afro-Islamic diaspora fashion industry.

Writing for BlackAmericanMuslim.com, Wheeler says that she intends to explore how the NOI and Imam W. Deen Mohammed (the son of former NOI leader, Elijah Muhammad) encouraged fashion shows, textile classes, and opportunities for women to monetise their talents in design to promote Black self-determination.

Black Muslim women’s participation in the natural hair movement can also be an interpreted as a form of resistance against capitalism’s demonisation of the Black body and Black cultures. Eurocentric ideas of capitalism have a pernicious history, with exploitation at its apex.

As Hortense Spillers explains in Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book, the Black woman’s body has provided, and continues to provide a parallel to the construction of white European and American women’s bodies. That is to say every component of the Black woman’s body is othered to accentuate not only the idea of a ‘default’ or superior femininity, but its own alleged inferiority.

In other words, beauty standards within the dominant white paradigm downgrade those who do not physically match or sustain the myth of ‘Eurocentric beauty’ as the standard.

The ‘Black Is Beautiful’ movement, propelled by the Black Panthers, was a powerful attempt to challenge and subvert the notion of ‘Eurocentric beauty.’ It popularised the Afro, worn by the likes of activist and academic Angela Davis, musician Nina Simone, and The Jackson Five. The current natural hair movement is inspired by such earlier efforts; and stands against rampant capitalism which has racketeered Black bodies and culture, and continues to do so to this very day.

Misguided ideals around Black beauty also extend to how Black women should best treat their hair. Nigerian-Irish academic and broadcaster, Emma Dabiri, suggests in Don’t Touch My Hair that colonialism has played a role in creating the perception that dealing with one’s natural hair as a Black woman is arduous and time-consuming. Speaking about braiding she says, ‘I’m reluctant to describe this process as time-consuming because I’m keen to disrupt our deeply ingrained (yet recent and culturally specific) myth of time as a commodity…It is a process that brings people together and facilitates intergenerational bonding and knowledge transmission.’

It is a sentiment that twenty-nine-year-old Rwandan who works for Accenture, Nabiirah Kaseruuzi, shares:

It’s a matter of self-love to have the patience to do your hair when you come out of the shower even though you know it will be covered. There’s always a temptation to be negligent about maintaining your hair when you first start wearing hijab, and I was no exception. The question I had to ask myself is when I maintain and style my hair, is it for me, or the approval of others? I was taught the importance of self-care from a young age, so learning to groom my hair regularly, regardless of whether people see it or not, became a priority. Doing this brings me joy and makes me feel even more gratified to be a hijab-wearing woman.

Imani explained to me that she did not always veil, but that she appreciates how finding the time for hair has little correlation with the decision to cover. ‘I love getting my hair done when I have the opportunity to do so, and I think more so me being a mum and not necessarily having time to do it is as a result of that and not necessarily because I wear hijab. Now granted, I do make sure that I go at least once every two months and I get my hair blown out by my Dominican aunties.’

However, when thirty-year-old Khadijah Antron who is Afro-Latina, first converted to Islam and decided to wear hijab, she found it challenging readjusting her hair care regimen – especially while living in Turkey, a Muslim majority country with a small Black population. ‘I didn’t have to cover my hair [before],’ she recalls. ‘Covering it causes it to dry [out] because Turkey doesn’t have certain under-scarves. The ones they do sell are expensive and there isn’t much in regards to hijab products that cater to natural hair and Black women. But I do all this for Allah and hopefully, the [wider] Muslim community considers [catering to] natural hair women.’

While countries like the United Kingdom and the United States are increasingly receptive to the appearance of Black women’s natural hair, and styles such as braids, Afro puffs, and locs, some Black women complain about the lack of appropriate hairstylists and products in the areas they live and work, otherwise known as ‘Black Hair Deserts.’ In an article in Allure, sociologist Shatima Jones says that demographics, class, property costs, and gentrification all play a role in making Black Hair Deserts, which are ‘a function of suburbs.’ ‘Who gets to live in the suburbs? Who gets to own a home? That’s definitely a class dynamic, which [in] the United States, is closely tied to race’, she says. In Khadijah’s case, the gap between race and accessibility widens further in Muslim majority countries such as Turkey, where Black immigrants make up a smaller proportion of the populations than in Western European countries. But Black Muslim women are at a greater disadvantage in such cases.

Somalian-Australian academic Najat Abdi says:

As a Black Muslim woman raised in the Western world, we often come into contact with other brothers and sisters who are also of immigrant backgrounds, but may not necessarily understand the process of styling and maintaining Black hair. There are many salons that offer chemical straightening and other procedures aimed at vanishing the tightly wound coils of 4B or 4C hair, but rarely a salon where Muslim stylists have knowledge of Black hair care.

To address these issues, Black millennials are establishing online companies and smaller businesses that cater to Black women and their hair in western European countries.

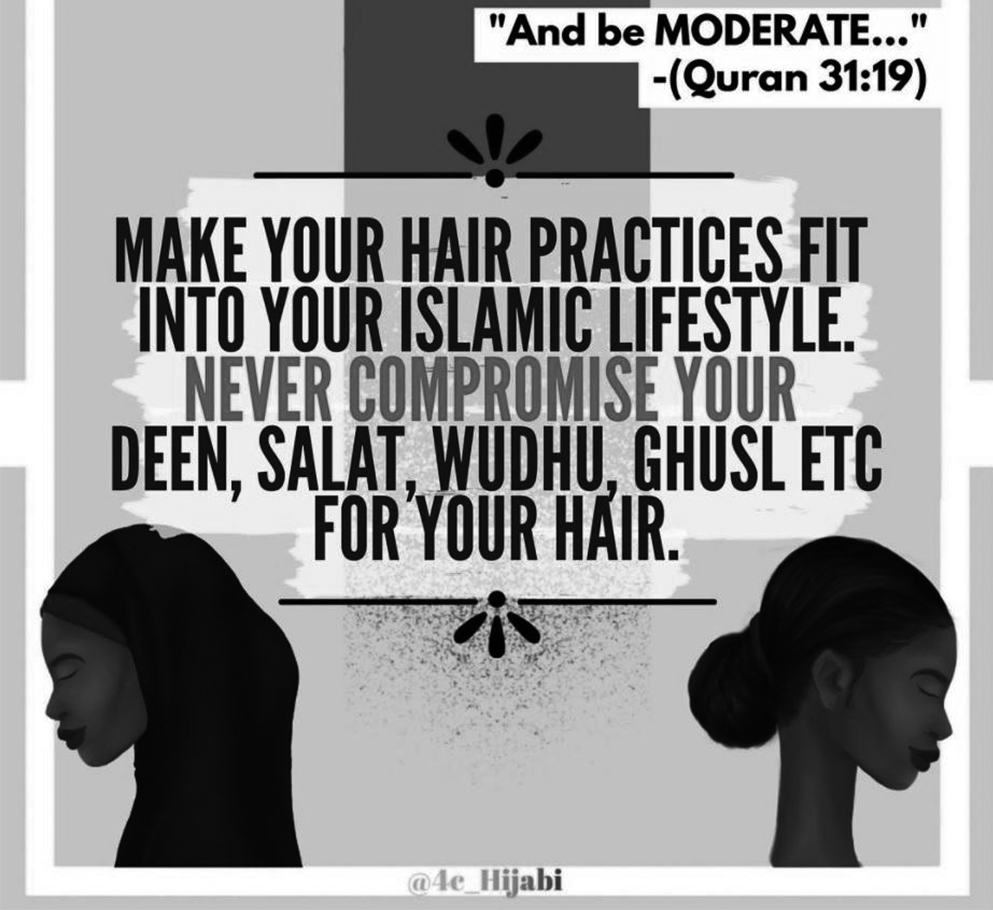

In Britain, for example, companies like Afrocenchix are leading the way in providing suitable natural hair care products for Black women that are not easily found in mainstream cosmetic and beauty stores. In Brazil, Beleza Natural is one of the most important hair franchises catering to women of African descent. Social media too plays a crucial role for the black hair care community and its customers, and conversations are being had amongst Black Muslim women who are carving their own spaces online to navigate their ‘coils, kinks, and hijab pins.’ One of these is the Instagram platform 4C Hijabi (@4c_hijabi) that educates Black Muslim women on the science of hair growth and how best to take care of ‘hijab hair’. These include tutorials on hijab-friendly styles, and a hijab edition of product reviews and podcasts. Its founder, RaySunshine, is a British-Nigerian living in Liverpool who started the platform in 2018.

RaySunshine explains that she simply wanted healthier hair but found it difficult to find resources which catered to Black Muslim women who wear the hijab. So 4C Hijabi was born. ‘I have nothing against relaxing hair safely or straight hair, but I just find it odd so many of us don’t know how to care for our natural hair. How can I say that I cannot take care of the hair that Allah has given me? I really wanted to understand the science behind it and when I found my natural foundation was solid, I started thinking I am a Muslim, I can’t be doing frohawks under my hijab!’

But the issue of styling is not the only concern for Black Muslim women who cover their hair. There are other problems too.

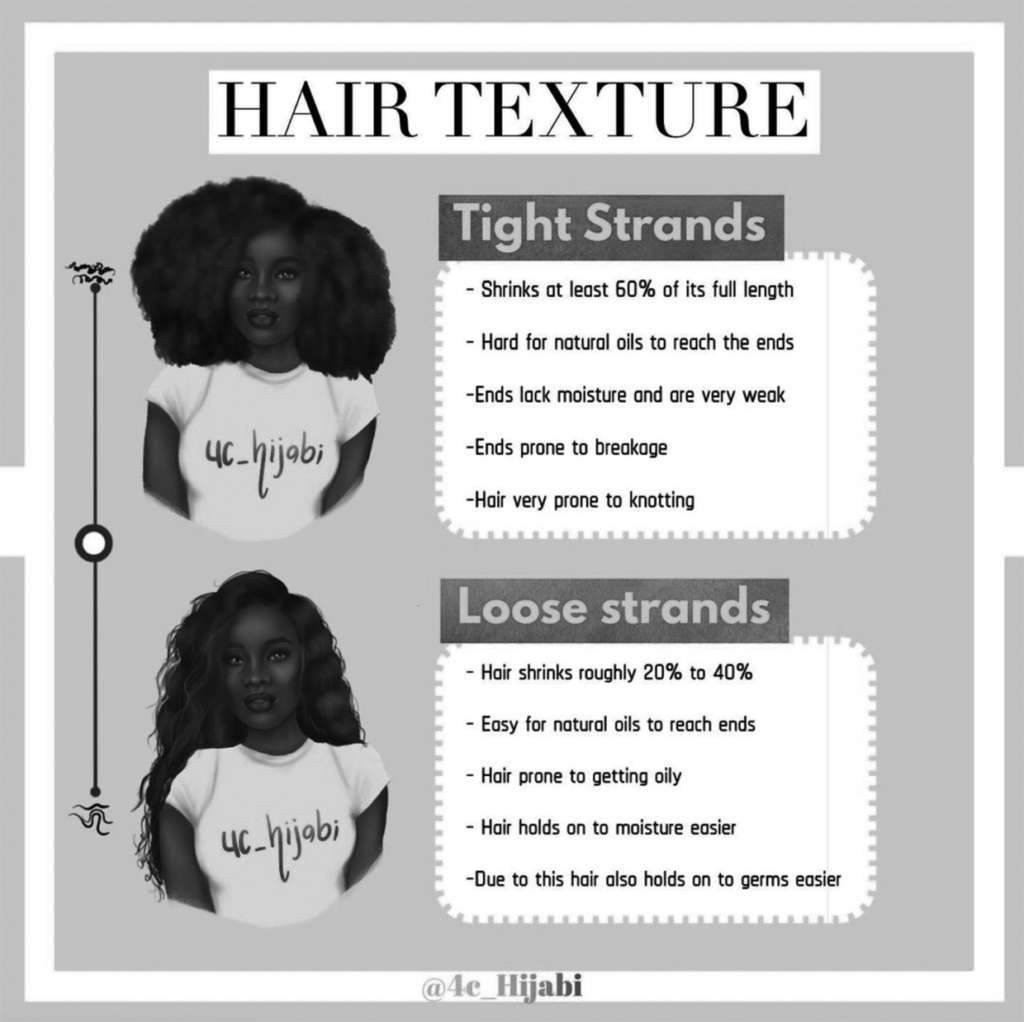

As Tennessee-based, Khadijah Abdul-Haqq, author of Nani’s Hijab, explains in a tweet: most fabrics ‘snatches [sic] our hair’ and ‘then there is a whole thing with oil stains on your scarves. Not to mention braids and what styles to wear at that time of the month. Black Muslim women hair drama never ends.’ ‘That time of the month’ is a reference to menstruation, whereby Muslim women are exempt from praying, fasting, and having sexual relations with their spouses. The latter has implications for Muslim women generally as a special bath is performed afterwards – and this includes wetting the hair. This means that Black Muslim women may feel more conscious about what kinds of hair styling they utilise outside menstruation. Generally Black women have Type 3 and Type 4 hair curls that tend to be drier, curlier, and do not retain moisture easily, which means Black Muslim women have to pay particular attention to the types of fabric that constitute their head coverings. Most Black hair care websites such as Naturallycurly.com advise minimal exposure of the hair to cotton and the use of satin or silk on the head while asleep.

Black Muslim women, like other Muslim women who wear head coverings, often hear questions about their hair and hijab. ‘Do you wear that in the shower?’ ‘Do you ever take that off? ‘Do you even have to take care of your hair under there? But Black Muslim women also hear a question that their Arab and Asian counterparts do not: ‘How long is your hair?’

Personally, I remember younger Muslim girls at a mosque in South London asking their Black friends about the length of their hair and the latter’s uncomfortable facial expressions.

While Black hair grows at the same rate as other human hair types, the idea that longer ‘flowy’ hair is desirable, is a function of Eurocentric beauty standards. Black Muslim women generally sit between this and the anti-Blackness and texturism from some Asian and Arab communities over what is considered ‘good hair.’ ‘I remember taking off my hijab at my friend’s engagement party of mainly Pakistani women, many of whom were wondering what’s underneath my hijab – me being a Black Muslim woman. When I did, someone told me to simply put it back on’, says RaySunshine. But texturism and colourism can manifest itself for some Black Muslim women in other ways too. As Najat explains:

As a Muslimah of East African descent (specifically Somali), I come from a region of the continent where women exhibit wide variations of hair textures. My late father had very curly, coiled hair, while my mother has straight hair. Growing up amongst our communities here in Australia, one does see texturism being played out. There was always this quest to obtain silky, straight hair.

Living in Australia and the constant representation of white women with straight hair being the so-called ‘ideal’, it had social, economic and romantic implications for Black women. As a teenager, I witnessed a pattern where sisters with Eurocentric features were given opportunities to progress. Despite the privacy the hijab provided, it was a common assumption that if a Black sister had lighter skin, and a narrow nose, then she had to have long, straight hair. Colourism and texturism were very much interconnected.

Such issues highlight the complexities Black Muslim women face regarding their hair; and how they are navigating these in keeping with their faith. It is not particularly easy when colonial legacies, as well as Islamophobic rhetoric mean Black Muslim women’s femininity is always a target. But beauty and Islam are not anathemas. In fact, hair care is praiseworthy and is considered an act of worship that is rewardable. And while Black Muslim women share hair narratives with other Black women, it is exciting to see how they are also forging a whole new discourse by and for themselves.