He stumbled out from in between two corrugated-iron and wooden huts, onto the pavement and spun round to face me. I was walking towards him along one of the miles-long straight highways that bisect Detroit’s suburbs. Detroit: Motor City – built by cars and built for cars. Home of Ford, GM, Chrysler, Motown records and the Nation of Islam. There was no one else on the Rustbelt stretch of road, only him and me.

He came into focus as I got nearer to him. White guy in his late sixties, swaying gently, wearing loud check golfing trousers hiked up round his belly button and a dirty-coloured T-shirt through which his scrawny arms poked. A few yards further and I could make out his creased and stubbled face, with yellow flecks of spit dried at the corners of his thin lips.

He wants some money. The story pours out – he was homeless and had been sleeping on the sofa of his nephew’s shack (or ‘holiday home’ as the improbable sign facing the road would have passers-by believe) but his nephew was a crack-head and he had beaten him up and stole his monthly social security cheque to score some rocks and now he was properly homeless, but his sister on the other side of the city had said she would put him up and he needed five dollars for the bus. I gave him the $5. I asked him his name – it was John – and he asked me mine. ‘Hassan? – are you a Muslim?’ I realised he hadn’t had a proper conversation for a long time. ‘I was in Vietnam. I would never go to Afghanistan or Iraq – those fuckin’ bastards have really messed it up for the Arabs. I know you are good people, I don’t care what they say – Mohammed was a good man and I believe he ascended to heaven’.

The conversation had taken an unexpected turn. I asked him about himself and found out that he had worked for twenty-five years on the assembly line at the historic Ford River Rouge car-plant, just three miles further down from where we were standing. But he had become an alcoholic and had been sacked for coming on shift drunk one time too many, so that not even the union could save his skin. ‘I’ve done terrible things because of drink’. His family didn’t like him talking about Islam but he didn’t care. He had read the Qur’an – it was a good book and he knew that it didn’t have chapters like the bible, it had soo-rahs. ‘Soo-rahs,’ he repeated.

I was thinking of asking him what he thought of his city’s bankruptcy and extreme decline – the factory closures, the shrinking population, the evictions, the corruption, the poverty, the dereliction and devastation – but I stopped myself. What would be the point of asking the man about the disintegration around him when he was disintegrating from within. We parted. ‘Allah bless you,’ he called after me.

The River Rouge plant that had taken a quarter of a century of John’s life before slinging him out was the largest factory in the world when it was completed in 1928. Located on reclaimed marshland where the Rouge River runs into the Detroit River, it was a short walk from Henry Ford’s childhood home in Dearborn, Michigan. Twelve miles west of downtown Detroit, the River Rouge plant was once a factory-opolis. It was a mile and a half wide and a mile long and had its own railway with sixteen locomotives and 100 miles of internal train-track, a fire department, a police force and a hospital. At its height in the 1930s it had a population of 100,000 proletarians, making sure one car rolled off the assembly line every 49 seconds. To secure the resources to shovel into its maw, the Ford Motor Company bought up coal mines, forests, iron mines, limestone quarries and a rubber plantation in Brazil. As Ford biographer Robert Lacey writes, Henry Ford ‘had the vision of a total plant, the ultimate factory, where the raw materials poured in at one end and the finished cars came out at the other’.

At night the River Rouge still gives the appearance of an industrial cauldron; tall chimneys capped by gas flares, dots of glowing red lights blinking from the tops of giant sheds and the occasional rumble of freight trains leaving the plant. But it is a nocturnal illusion. Today the River Rouge plant employs just 6,000 people and is marketed as a museum destination, giving visitors ‘historic’ tours of the plant. This is emblematic of the decline in the city’s auto-industry. In the 1950s the Motor City boasted of 300,000 auto jobs across thirty-three factories, swelling the city’s population to 1.8 million. Today the city has shrunk to 700,000, with auto jobs reduced to 27,000. There are now more casinos than car factories in Detroit.

In July 2013 the city was declared bankrupt. It was the largest municipal bankruptcy ever filed in US history by debt, estimated at $18–20 billion. Was this city, once the heartland of industrial capitalism, actually dying? Would history be played backwards, and land upon which Detroit sits revert to the marshland, meadow, scrubland and forest it once was? Could such a thing be allowed to happen?

Going through passport control at Detroit Metropolitan Wayne County Airport I had been grilled by a bad-tempered immigration officer. What is my business in the city? Do I want to tell him I am writing an article for a publication called Critical Muslim? I tell him I’m just visiting the city as a tourist. He shakes his head. No-one comes to Detroit as a tourist. Try again. I’m an artist and I want to see the city’s cultural destinations. Like where? Try again. I’m a freelance journalist researching a piece on a city in its death-throes. He grimaces ‘Don’t you have places like that back in the UK you can write about?’ No, not really. Now he’s insulted, but it’s the most credible explanation thus far. He lets me through.

Detroit is an international cultural destination – of sorts. Its blighted inner-city landscape, a canvas of deserted houses, shops and buildings, is a magnet for graffiti artists everywhere. One website, detailing where to find ‘35 must-see pieces of Detroit’s exploding street-art scene’ points out that ‘in case you haven’t noticed, Detroit has become one of the most vibrant centres of street art in the country in recent years. Hundreds of authorised murals by some of the most famous street artists in the world now grace downtown, Eastern Market, southwest Detroit, the Grand River corridor and other hotspots’.

I follow the tour – parking my hire car on Grand River Avenue one mile before it hits the city centre. I walk the Grand River Creative Corridor (GRCC) Project – an outside gallery of graffiti pieces displayed along the roadside and on walls by local artists. I like some of it. But I am drawn to a giant mural just outside the ‘corridor’, painted on the side of an abandoned warehouse. It is a series of portraits of figures from Detroit’s civic past. I find out later that the artist wanted to show ‘everyday kind of people, people who fought on behalf of their fellow citizens’. I’m taking it in, when out of the corner of my eye I see a middle-aged African-American man walking down the steps of the only property around that isn’t abandoned, his hands full of stuff which he dumps in the trunk of an old car. I wonder what he thinks of the mural and does he know who any of them are. He doesn’t, but he likes it. His name is Joe and the building he has just stepped out of is a hostel for the homeless. He’s a nice chatty guy. I find out that he spent nearly twenty years driving an 18-wheeler monster truck, delivering auto parts to every state in the union. He tells me he loved the job – even though the pay wasn’t that good because he was employed by a non-union trucking company. He becomes energised. ‘You had to really concentrate you know, driving an 18-wheeler in the snow and the ice, it was hard work.’ Pause. ‘But sometimes I miss it,’ he says softly. One day he had a terrible crash that left him disabled – he had to have a hip replaced and his shattered pelvis bolted back together. His driving days over, his only income was his state disability payments, and when the rent for his flat went so high he couldn’t afford it, he had been forced into homelessness. For the past three months he had been living in ‘transitional accommodation’, hoping to be re-housed.

Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry mural

We say goodbye and I walk down Grand River Avenue towards downtown (central) Detroit – I’ll be amongst the skyscrapers in maybe ten minutes. I pass by a small spotless whitewashed building. It’s the Moorish Science Temple of America #25. It is locked up tight, and painted on the walls are fez-topped life-sized silhouettes, as if silently standing guard. On the back wall is a huge poster with the Moorish American Prayer: ‘Allah the father of the universe, the Father of Love, Truth, Peace, Freedom and Justice. Allah is my protector, my guide and my salvation by day and by night thru his Holy Prophet Drew Ali. Amen.’ I am reminded of this particular strand of Detroit history; how the Noble Drew Ali had founded the Moorish Science Temple in Chicago in 1913, declaring that African-Americans should embrace their true nationality as Moorish-Americans and their true religion: ‘Islamism’. When Drew Ali died in 1929 the leadership of the organisation broke up. One former Moorish Scientist, calling himself Wallace Fard Muhammad, then resurfaced in a poor black area of Detroit called Paradise Valley, founded what became the Nation of Islam and laid down its creed. He disappeared four years later, in trouble with the Detroit authorities, after one of his followers was detained (and later found to be insane) after committing human sacrifice to ‘bring him closer to Allah’. The leadership was then taken over by Elijah Muhammad, who spent the next few decades building it into a national organisation. On the other side of Grand River Avenue still stands Nation of Islam (NOI) Muhammad Mosque No.1, as a reminder of the NOI’s Detroit roots.

Joe outside his hostel

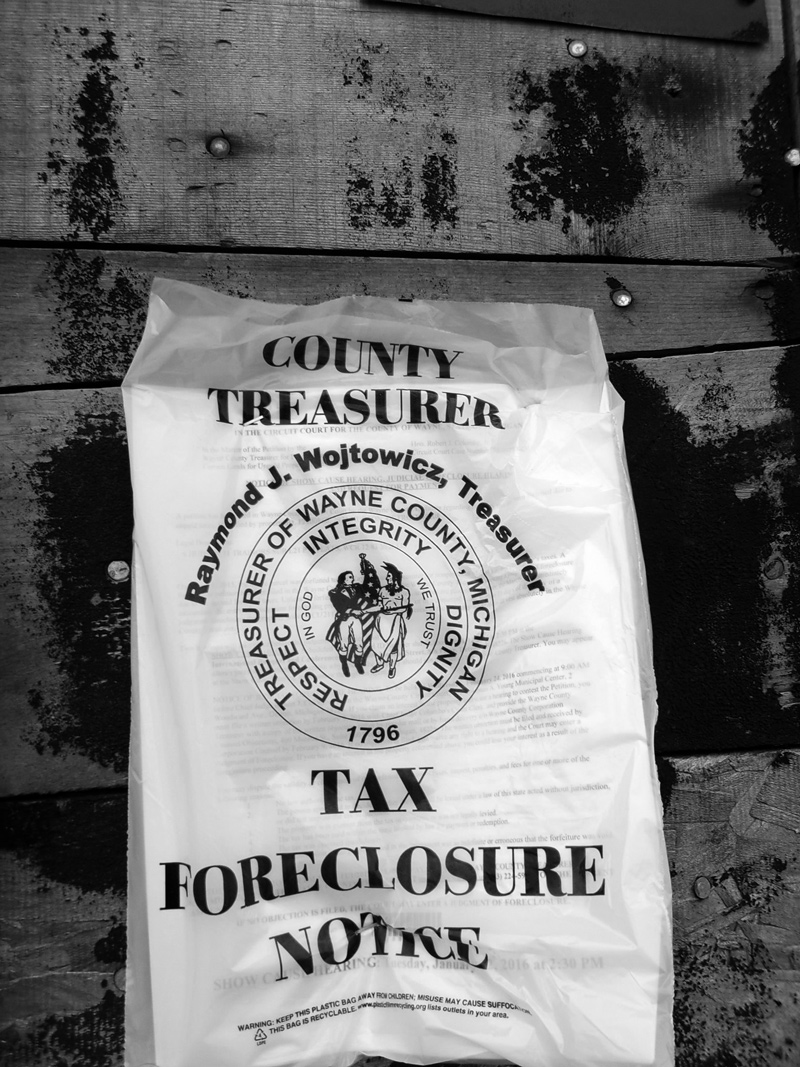

Just across from the Temple, set back from the road, I see a pair of boarded up derelict wooden houses. Stapled on the front of one of them is a yellow bag: Tax Foreclosure Notice. I will see many, many more of these court orders over the next few days – badges of shame pinned to broken-down homes from which the occupants have fled or been forced out. I pull the bag off and read the court papers inside. It tells me that the County Treasurer was ‘seeking a judgement of foreclosure due to unpaid taxes’ – in other words seizing the house because the occupants owed the county property tax arrears of, in this case, $1,095.61 (£760). The person, or persons or family who lived there had clearly moved out before suffering the indignity of being evicted, as the court hearing was not until the following month. What had been someone’s home was now an abandoned lot.

Tax Foreclosure Notice

The Stagecoach from Hell

Detroit Eviction Defense meet every Thursday at Old St. John’s church (‘FOR WITH GOD NOTHING SHALL BE IMPOSSIBLE’), close by the trendy Eastern Market, just north of the city centre. I push open the church door and come across a huddle being briefed on property law. Next door the group’s organising committee are sat talking tactics – specifically how to avoid being arrested on a protest planned for a couple of days’ time. Detroit Eviction Defense describes itself as ‘a coalition of homeowners, union members, faith-based activists, community advocates, and allied groups united in the struggle against foreclosure and eviction. We believe that affordable housing is a human right, the foundation of a viable community’.

Detroit Eviction Defense mural

A couple of the committee acknowledge my presence with a nod and smile, and I take that as an invitation to sit down and listen in. I look round the group, trying to assess their activist ‘type’. Most, but not all, are middle aged or nearing retirement. Do the maths: the ’68 generation who came of age during the anti-Vietnam protests and the civil rights movement. Or even earlier. After the meeting I get into a wide-ranging conversation with a very nice older woman. She explains how speculators large and small were buying up parcels of Detroit cheap, how the apartment she lives in had been bought ‘by some person in Australia’ who had never seen it. The reason why there was no public transport infrastructure serving the city was down to the auto-plant giants, Ford, Chrysler, GM, who had blocked it because they wanted everyone to drive their cars, and now one third of the kids in Detroit were suffering from asthma. Her name is Dianne Feeley. Later I discover that she had been politically active even before 1968, was involved in the women’s liberation movement in the 1970s and was now a retired auto-worker. In 2011 she had been heavily involved in the Occupy movement in Detroit; part of the global protest against social and economic inequality. Detroit Eviction Defense was a logical spin-off from Occupy Detroit – given the crisis of hurricane-like proportions that was laying waste to the city’s working class households, of which 82 per cent were African-American. Between 2002-2008 there were 19,000 tax foreclosures. Between 2008-2014 another 94,000 homes went the same way. The majority of properties were now owned by the city, it only managed to sell on a few thousand, meaning that the rest quickly fell into disrepair or were pulled down. In fact, more homes have been destroyed in Detroit than were swept away in New Orleans by Hurricane Katrina. And the process is speeding up – last year alone another 62,000 Detroit properties were in line for having the yellow plastic sleeve stapled to the door.

One Detroiter described the nightmare that stalks working class neighbourhoods as a result of the foreclosures – The Scrappers. Literally minutes after a poor family has been evicted and the bailiffs and police have driven off, bands of scavengers descend on the still-warm dwelling and dismember it. Water and heating pipes are ripped out from under floorboards and out of walls, leaving water spewing from the mains, the doors and windows and sills are prised away, the wiring pulled out like sinews from flesh, sinks, baths, toilets, taps – whatever can be carted away. One policeman told the press: ‘We’ve seen a four-storey apartment building stripped clean in a week’.

A sunny November Sunday morning a couple of days later. I park the car up. The street is deserted. The pleasing sound of a gospel choir drifts out from a nearby Baptist Church. On the corner of 16th and McGraw in the NW Goldberg area of the city – just a seven-minute drive from the banks and department stores of downtown Detroit – sits the ghost of someone’s home. The front is hidden by a tangle of weeds and bushes. I push my way through and climb the steps onto the front porch. Laying on its side is a broken rocking chair.

Stepping through the doorway (sans door) I enter the house. It is gloomy and depressing – an old rotting mattress in a downstairs room, kept company by a cheap swivel chair. I avoid a gaping hole in the corridor floor where the strippers have burrowed for copper piping.

Corner of 16th and McGraw

I climb the stairs carpeted in flakes of plaster that has peeled away from the wall. The upstairs is wrecked; there are holes punched in the ceiling, holes in the walls, and empty spaces where the upstairs windows once were; giving me a view of the equally ruined house next door, with its stapled yellow bag, close enough for me to read the proud slogan of the Treasurer of Wayne County, Michigan, Raymond J Wojtowicz: ‘RESPECT, INTEGRITY, DIGNITY’. Standing in the wreck I try and imagine the family that once lived here and conjure up the sound of their voices, but it’s impossible because the structure no longer has a scintilla of home-ness remaining.

On to Manistique – an enviably situated road in a blue collar neighbourhood on the Lower East side of the city, bordered to the south by Detroit River as it flows out into the 430 square miles of Lake St. Clair, and to the east by the exclusive Grosse Pointe waterfront area, home of the city’s ‘old money’ families, along with their ‘preppy’ Ivy League offspring. Edsel Ford, the only son and heir of Henry Ford, once lived in Grosse Pointe.

Strippers at work

839 Manistique is the childhood home of fifty-six-year-old hospital dialysis technician Lela Whitfield. She sits on a chair talking to a friend outside the well-maintained bungalow, surrounded by cheery members of Detroit Eviction Defense, who have called this Sunday afternoon gathering to protest at Lela’s imminent eviction. They have pledged to organise a 24-hour watch on Lela’s home and blockade it to stop the bailiffs seizing the property, throwing her possessions in a dumpster and turning her out onto the streets. It is not difficult to imagine what would then happen. On one side of Lela’s home is an empty overgrown lot upon which a house belonging to Lela’s neighbours once stood. It was pulled apart by the scrappers. There is now not a single plank of wood to mark that a dwelling once stood there. I sense that this was once a proud African-American neighbourhood; home to generations of independent-minded home-owners who would sit on the stoop hailing the neighbours and keeping an eye on the kids riding up and down the road on their bikes. But it has taken a big hit and has been brought low in ways the residents could never have imagined, and now they struggle to keep their community together and maintain their confidence and dignity.

Lela Whitfield (left) and friends

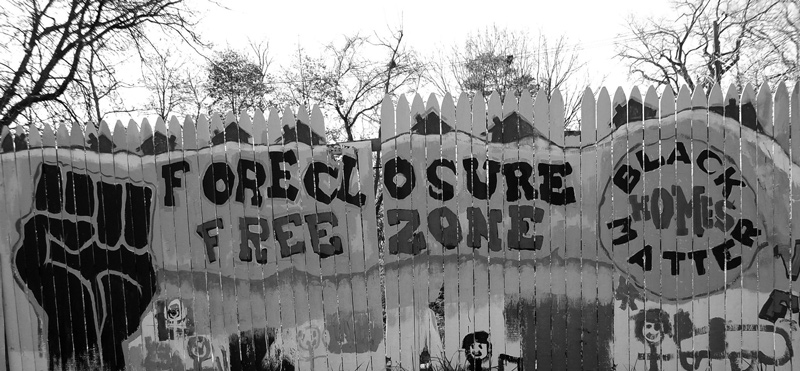

On the other side of Lela’s is another empty plot, enclosed by a white picket fence on which a number of vivid murals have recently been painted with the slogans: ‘Foreclosure Free Zone’, ‘Black Women’s Lives Matter’, ‘Black Homes Matter’ and ‘Ain’t we got a right to the Tree of Life?’

Lela’s story is shocking, and tragically commonplace in today’s Detroit. She grew up on Manistique, left to live her life and then moved back about fifteen years ago to tend for her ailing mother, who died in 2010. It was only then that she found that her mother had taken out a ‘reverse mortgage’ loan on the house she owned – a vicious financial instrument that lenders waved in front of the US’s older African-American population through late night TV info-mercials and celebrity endorsements. This demographic was rendered susceptible to this hard-sell due to falling incomes and a soaring cost of living. Last year alone 12,000 Detroit retirees had their pensions reduced by upwards of 7 per cent to help pay for the city’s bankruptcy.

Reverse mortgage TV hucksters included country crooner Pat Boone, actor Robert Wagner and Henry ‘Happy Days’ Winkler – ‘Everyone trusts the Fonz’. In 2005 Lela’s mum fell for their patter and took out a loan against her house. She didn’t tell her daughter – I suspect she was too proud to reveal what she had done. A Detroit Free Press briefing explains: ‘A reverse mortgage starts when a homeowner receives a loan that gives the lender an ownership stake in the property. A reverse mortgage loan requires no repayments when the borrower is alive. That’s usually a senior citizen on a low income and needing cash to make repairs on the house, cover medical expenses [or] pay off accumulated taxes. The homeowner makes no payments, but interest rapidly, ominously, mounts on the loan balance. When the homeowner dies, that outstanding balance can turn out to be the value of the house’. A wicked, wicked invention of Wall Street.

When Lela found out about her mother’s reverse mortgage she offered the loan company, Fannie Mae, $9,000 – the market value of the house. But they refused to sell it back to her, preferring to continually drag her to court, demanding possession of the property. The debt ballooned to $60,000. In desperation Lela turned to Detroit Eviction Defense – and they have rallied to her. She smiles as speakers at the protest excoriate Fannie Mae (the Federal National Mortgage Association) for its predatory practices and vindictiveness. Fannie Mae was an invention of the Great Depression; originally set up as part of Roosevelt’s New Deal to boost home ownership by providing reasonable mortgages. It has turned into its opposite. In the 1990s President Clinton forced it into the ‘sub-prime’ market, a disastrous turn that detonated the huge financial crash of 2007–8, forcing the US administration to bail out Fannie Mae and its sister company Freddie Mac, to the tune of $360 billion and nationalise them. Lela is determined and resilient – at least outwardly. ‘I’m not looking for sympathy or empathy’, she tells me. ‘I was forced to do this. It’s hanging over me and it’s not a good feeling. But I have no fear.’ She sighs. ‘They want to evict me from my home. They should allow me to continue to be part of this community’. Lela nods to the empty plot next door. ‘That was a nice home’. Her friend Shawn nods vigorously and both women reminisce about the family that ‘used to live there’. I ask Shawn what happens to all the people who ‘disappear’. She shrugs her shoulders. ‘You see them panhandling in front of stores and getting harassed by the police. But they’re not drug-addicts – they’ve just come on hard times.’ Hard Times indeed.

Matt Clark, the lawyer attached to Detroit Eviction Defense, has a clear view of the forces at play in Detroit behind the mass evictions. ‘Parts of this city look like a bomb has hit it.’ But he argues that this was not the result of an off-target missile strike or a force of nature; this was done by people who knew what they were doing. He informs me that sixty-eight per cent of loans issued in Detroit were sub-prime.

Matt says that staff in one loan company, Wells Fargo Bank, privately referred to reverse mortgages as ‘ghetto loans’ and the recipients ‘mud-people’. He is telling the truth: A lawsuit against Wells Fargo revealed that the bank pushed expensive subprime mortgages onto blacks and Latinos, even though many of them qualified for less punitive deals. So, for example, those who took out a $165,000 mortgage had to pay $100,000 more in interest then white clients in a similar financial position. Special sales teams targeted black church leaders, knowing they could be used to persuade their congregations to take out expensive loans they would inevitably default on. They did indeed use terms like ‘mud people’ for their victims. As one ex-seller put it, Wells Fargo ‘rode the stagecoach from hell’. Matt has been fighting Fannie Mae through the court on behalf of Lela Whitfield for two years. I ask him why the government-controlled company didn’t just settle with her, and take the money she is offering, rather than taking control of what is to them a worthless property. ‘They don’t want to keep occupants like Lela in their homes. They call it “a moral hazard”.’ In short, the free market, neo-liberalism, whatever you want to call it, must be seen to run its course unimpeded by any human consideration. To do anything else, to let off the hook those wriggling on it, contravenes the logic of the market, and is therefore deemed ‘immoral’ in this most capitalistic of countries. Matt helps Detroit Eviction Defense precisely because ‘they don’t back down against the most powerful organisations in the world. The banks are used to having their way, but we have found them to be very vulnerable when they have to call out the police to evict someone’. He is clear about the limits of the law: ‘As an attorney I have come to understand the argument won’t be won by legal virtuosity.’ His view is strengthened a few days later when a court hearing, packed by Lela’s supporters, sees a Detroit judge give a stay of execution, and order that both sides enter talks. Those present tell me this decision has completely wrong-footed Fannie Mae’s lawyers who had expected ‘victory’, having confidently argued that the giant lender was ‘merely living up to its legal and financial obligations’ in seizing 839 Manistique.

Across the road, sitting on a porch watching the protest, are two young African-American men – Travis Thompson and Jabari Anderson. They talk to me about the ‘golden years’ of Detroit, how African-American families built their lives on the wages they earned at Ford, GM and Chrysler, built up neighbourhoods and communities, owned their homes, educated their kids and looked forward to their well-earned retirement. They did not foresee that the city’s car industry would uproot itself and move south in search of cheap wages and higher profits, the economy fall apart, the city go bankrupt and finally the scrappers move in and literally take apart all they had achieved – leaving an urban wasteland. ‘In the best times every house on this block was so nice,’ says Jabari. But nowadays, adds Travis, ‘you see people go – friends you have known for years, older people who led the community. It takes the spirit out of you – it brings you down.’ Jabari casts his eyes around the overgrown lots: ‘It looks like the countryside – you’ve got deer and coyote running through the middle of the city.’ (Coyotes are becoming an urban problem in Detroit, with reports of them hunting in packs and eating people’s house dogs, large and small.)

Travis felt like moving on, but knew that running away wouldn’t solve the problem. He summoned up a feeling of self-reliance – a kind of twenty-first century version of the frontier spirit that drove the French fur trappers who founded the city back in the early eighteenth century. Abandoned by national and local politicians, abandoned by the banks, the city authority and even the retail sector who have moved their shops away, ordinary Detroiters have been forced to fall back on their own resources. ‘We provide for our own people; we are not asking for help,’ says Travis. ‘We realise it’s up to us. We can’t look up to our own leaders any more.’ Jabari jumps in: ‘They’re not helping us, they’re hurting us. They’re so corrupt!’ He is referring to the Kwame Kilpatrick scandal. Kilpatrick became Detroit’s youngest ever mayor when he was elected in 2002, at the age of thirty-one. From a family of black Democrat career politicians, the flamboyant Kilpatrick declared at his inauguration, ‘I stand before you as a son of the city of Detroit and all that it represents. I was born here in the city of Detroit, I was raised here in the city of Detroit, I went to these Detroit public schools. I understand this city. … This position is personal to me. It’s much more than just politics.’ What the voters of Detroit didn’t realise was that the ‘personal’ meant embarking on a programme of enriching himself, his family and his cronies through a lavish and dissolute lifestyle paid for by the city and via bribery, kickbacks, embezzlement and the mining of city contracts totalling millions of dollars. His response to those critics who sought to reveal his corrupt dealings was to play the race card; appealing to black Detroiters as a ‘nigger’ being pursued by a latter-day lynch mob. Kilpatrick is presently serving twenty-eight years in prison, after being found guilty of ‘pattern of extortion, bribery and fraud’. His earliest release date will be in 2037, by which time he will be sixty-three years old.

So, one day Travis decided to cultivate the empty plot next door. He showed me around his urban farm, started in 2009, which is now in its winter dormancy. In the summer he grows tomatoes, lettuce, grapevines, squash, carrots, aubergine, watermelon, strawberries and hot peppers. He sells or gives most of it away to his neighbours and the rest goes to town to be sold at the Eastern Market. School classes take trips to his farm, and visitors come from all over to admire it. There are now maybe 2,000 urban farms, large and small, across Detroit. The ‘greening of Detroit’ is in full swing, with the city selling off some of the 40,000 plots of deserted land they own to urban gardeners. The big auto companies, eager to generate good publicity to repair their dented image are in on the game – General Motors have converted 250 shipping crates into raised-bed planters, creating the ‘Cadillac Urban Gardens’.

But for Travis, his cultivation represents something quite profound. He tells me that ‘as it progressed I understood that it was a lot more than just growing food out of the ground’. Yes, it had a practical reason behind it – ‘what if they close the grocery stores?’ – but it was also symbolic. ‘It’s brought a bit of love and positive spirit to the neighbourhood, a little bit of hope amongst the heaps of rubble.’ For him it is about taking back control of his life and his environment. Its sweetness counteracts the bitterness that wells up inside Travis, a symptom of the abandonment and betrayal he and his friends inevitably feel.

After the protest I swing by the Grosse Pointe neighbourhood that begins just a stone’s throw away from Lela’s threatened home and Travis’s urban farm. I drive past mansions, manicured lawns, expensive cars and boats parked on the drives, with middle-aged white guys on their day off, out front, sweeping dead leaves into piles. I wonder whether long-term speculators have their eyes on the houses on Manistique, knowing that sometime in the future an expansion of Grosse Pointe will make the land very valuable indeed.

Dearborn

For most of the twentieth century the Detroit suburb of Dearborn was a company town, owned and run lock, stock and barrel by the Ford empire. Its height must have been in the 1920s and 1930s, for many of its prominent buildings, (like the historic buildings of downtown Detroit) are impressive examples of art-deco architecture. The houses that branch out from its main roads are very pretty dwellings indeed, and give off a tidy, contented feeling – although I notice that there are hundreds of foreclosed Dearborn houses for sale on real estate websites.

Dearborn was originally the destination for poor migrants drawn from towns and villages in south, central and eastern Europe (and Ireland). Outside Dearborn’s Italian-American club stands a statue to Christopher Columbus – the ‘god’ who blessed them with a chance of a New World…and a job from Mr Ford. However, there were never many African-Americans allowed into Dearborn – they were segregated into other areas of Detroit like Black Bottom, Inkster and Paradise Park. In the 1940s Dearborn voters elected the notorious Mayor Orville Hubbard ‘who built a political career lasting more than a third of a century on the well-understood and thoroughly redeemed pledge to “Keep Dearborn Clean’’’, according to Robert Lacey. Hubbard was not afraid to say publicly ‘If whites don’t want to live with niggers, they sure as hell don’t have to. Dammit, this is a free county.’ (In a subtler, but equally racist manner, real estate agents in Grosse Pointe operated a secret points system by which they debarred blacks, Jews, Greeks and Italians from buying property.)

The Arab American National Museum in Dearborn

We don’t know (although we might guess) what Hubbard would have made of the fact that today his fiefdom has become the celebrated home to the largest-Arabic speaking population in North America. Dearborn’s Arab-Americans – Lebanese, Yemenis, Iraqis, Syrians and Palestinians – today constitute some 40 per cent plus of its 98,000 population. As writer Mark Binelli puts it in his book The Last Days of Detroit, ‘The best restaurants in metropolitan Detroit, for my money, are here, along stretches of Warren and Vernor that feel like neighbourhoods in Damascus or Beirut, if either of these cities have mini-malls. As the state of Michigan continued haemorrhaging residents, one demographic experienced a minor growth surge, about five thousand new arrivals in the Detroit metro area in 2010 alone: Iraqi immigrants.’ Binelli, tongue-in-cheek, concludes: ‘So that was something. Dire though things had become, Detroit, apparently, remained a more desirable place to live than postwar Baghdad.’

In the library of the Arab American National Museum in Dearborn, I spot a recent issue of the DC Comics graphic novel series ‘Green Lantern’ on the shelves, nestled amongst religious, historical and philosophical tomes. In this superhero tale that began fictional life in 1940, a succession of humans become imbued with powers given by a ring forged by aliens. The latest recipient of the ring is Simon Baz, a Lebanese American Muslim from Dearborn. In his backstory, which begins on 11 September 2001, Baz and his sister Sira are persecuted – Sira has her hijab torn off by 9/11 vigilantes. Against the backdrop of Detroit’s financial crisis, Baz is fired from his auto plant job, discovers a talent for car-jacking, and one night steals a van, which to his horror he discovers is carrying a bomb in the back. He drives the van onto the site of the now closed-down car plant, where it detonates without loss of life. However, Baz, being Arab, is suspected of being a terrorist, arrested and is brutally interrogated. The Green Lantern Power Ring finds him, allowing him to bust out of captivity. And so it goes on! The storyline is written by Geoff Johns, who is a half-Lebanese Detroiter. It’s an inspired example of the huge, energising impact of Arab-Americans on Dearborn, Detroit and wider American society. Of course there are plenty of real life examples of famous Arab Americans celebrated at the museum – from scientists to writers and trade union leaders to politicians. But Baz should have his place as well alongside the others. Like other immigrant communities, they have had to fight their way into the American mainstream. But by the 1990s Arab-American Dearborn could boast that it had produced the CEO of Ford, a US senator and the head of the United Auto Workers union. However, due to the times we are living through, they can still find themselves under scrutiny as a ‘suspect’ community. While I was in Detroit the November 2015 massacre in Paris was carried out. The Dearborn community automatically steeled itself, and lo and behold, a few hours later came the death-threats and then calls from US politicians to bar the entry of anymore refugees from the Middle East ‘until we can find out what the hell is going on!’.

The Arab American National Museum does its bit in educating the visitor, with displays on Islam and Muslim heritage, the history of its community, as well as giving space for exhibitions with a bit more of a contemporary edge – such as the striking photo-portraits of young Somali men that I viewed in the museum’s art gallery. After I have gone round I chat with Katherine, the cheery young woman on reception. Her family come from a small village in Lebanon – ‘back home’ as she calls it. She had spent two years in Lebanon attending the American International School, but was now back in Dearborn studying medical case management. As well as putting in time at the museum, which she sees as an enjoyable duty, she volunteers for ACCESS (Arab Community Center for Economic and Social Services), a grass roots organisation that was ‘founded by a group of dedicated volunteers in 1971 out of a storefront in Dearborn’s impoverished south end’. Katherine had been out the previous week with an ACCESS team, boarding up abandoned houses and cleaning up garbage in the south end. She tells me she was named after a much revered older member of her family and the community – Katherine Younis-Amen, who was one of the original founders of ACCESS and of the museum.

In reality, the Dearborn community does not fit the one-dimensional stereotype thrust upon it by the bigots. It is very diverse – a mix of American-born and newly arrived immigrants, Arab and Chaldean, Palestinian, Iraqi, Lebanese, Syrian, Shia, Sunni, Catholic, Orthodox and Protestant, wealthy and working class, business men and business women, public-sector workers, civil rights activists and law enforcement county deputies. Out of this diversity has emerged a particular fusion of grass-roots social activism and entrepreneurial flair. Wider Detroit also exhibits aspects of this – created by the huge vacuum left both by the retreat of the state from the lives of the city’s inhabitants and the ravages of the free market.

Small business start-ups are popping up across the city; encouraged by a combination of favourable tax breaks, access to funding, cheap rental property, and the stark truth that Detroit clearly needs help from someone. I arrange a meeting with a couple of representatives of this new business culture: Amany Killawi and Chris Abdur-Rahman Blauvelt are happy to show me around Green Garage, the eco-friendly building in mid-town Detroit that houses a number of ‘third sector’ organisations, including LaunchGood – their Muslim orientated crowdfunding business. These two young Muslims aim to enter the space that the city’s disintegration has opened up: ‘It’s like a laboratory – a Silicon Valley for social entrepreneurialism’.

Chris and Amany take their religion to heart. For them, Islamic values are intrinsically ethical and progressive, and therefore Muslims have a particular role and responsibility in reviving the city’s social and financial fabric. LaunchGood is built on that which they hold dear. Their website states: ‘Too often we are constantly telling others who Muslims are not, that we rarely can tell them who we are. We are proud of our heritage as pioneers, inventors, entrepreneurs and bearers of all things good. We believe in Muslims doing great work that benefits everyone, not just Muslims.’

Amany and Chris of LaunchGood

They advise organisations and individuals on how to crowdfund for good causes; such as raising money for a new roof for the home of a poor family, donations for medical aid to Syria, funding the rebuilding of black churches recently burnt down in racist arson attacks in the southern states, and a fitness DVD for Muslim women. Chris and Amany take me to the local halal café for lunch where they tell me what they are trying to do. Amany’s parents left Syria in the 1980s, and after a spell in Louisiana, migrated to Detroit where they raised their family. She is clearly a product of Detroit’s activist and social justice tradition. Chris was born in Kuala Lumpur where his father was working at the time, educated in the US, and at fifteen converted to Islam, partly inspired by the biography of Malcolm X. Both cite 9/11 as a watershed moment in their lives, convincing them that their mission as Muslims was to ‘do good’. In its first year their organisation helped raise over $1 million for more than 100 projects across thirteen countries. They are now up to the $5.5 million figure. They eschew the corporate approach that has done so much damage to their city. Amany tells me, ‘Purely maximising profit is not sustainable; we believe sustainability lies in creating value in the community.’ Chris adds ‘Detroit has a do-it-yourself culture. That’s what we love about this city.’

They also see the value in alliances across the different embattled communities – for example, that Muslims must unite with the black community: ‘African-Americans have the cultural power here in America and the immigrant communities have the wealth. If you can come together, you can do more than government or private investors can.’ They connect with a bigger entrepreneurial hub – ‘Dream of Detroit’ – another Muslim-led initiative that is attempting to reverse the tide of foreclosures by buying up land and renovating houses. Its declared goal is to ‘build a dense, thriving community on the west side of Detroit based on prophetic values of compassionate living and concern for one’s neighbours’. Perhaps Dream of Detroit and LaunchGood represent the green shoots of a new Detroit? Or is the task too great and the city just too far down the line?

No place like Utopia

This issue of Critical Muslim examines The City from all angles – as historical memory, as an existing entity, as a concept, a metaphor, a dream and a living nightmare. Yet despite this panoramic range, it is hard to ignore a plain truth – something has gone horribly wrong. The dissonance between humanity’s needs and the twenty-first century city clangs in the ear. As David Harvey says in his book Rebel Cities ‘the traditional city has been killed by rampant capitalist development…driving towards endless and sprawling urban growth no matter what the social, environmental, or political consequences’.

Javaad Alipoor, in his imaginative contribution for this issue, ‘Utopia in Tehran’, argues that the classical utopian concept of the city in harmony with the needs of its inhabitants has, like Tehran, ‘become sprawling, contradictory and covered in the muck of history’s most violent century’. As Alipoor highlights, more than in any other period in history, cities today are the site of the struggle for and against ‘democracy’ and ‘rights’. Dictators fear the insurgent forces that cities contain, and yearn to control common spaces where people may gather, dominating them symbolically through statues and monuments. Peter Clark, writing lovingly of Istanbul, which for him is still ‘the capital of the world’, tells how Ataturk had a statue of himself raised on the headland Sarayburna in 1926, ‘but he only came to the city for the first time, full of apprehension, the following year’. In ‘Tashkent Odyssey’ Eric Walberg writes that in the post-Soviet period the president/dictator of Uzbekistan Islam Karimov opened a museum commemorating national hero Amir Timur on the site where a statue to Karl Marx once stood – and for good measure replacing ‘a quiet tree-lined park which was a beloved meeting place for ordinary Tashkenters’. Walberg paints a fascinating picture of his time in Tashkent, from where he began his personal journey to Islam, pushed down the road by the dictator’s brutality, and beckoned ‘by waking to the gentle adhan and the sweet Uzbek women offering a share in their iftar’.

David Harvey argues that the only way to seize control of cities from dictators and rampant capitalism and to ‘build and sustain urban life’ is to assert our ‘unalienated right to make a city more after our heart’s desire’. This heartfelt leap of the imagination is at the centre of Syima Aslam and Irna Qureshi’s contribution: ‘Festive Bradford’. They describe how they launched the Bradford Literature Festival as a way of wresting the identity of the city back from a powerful media, who, ever since the Rushdie affair, have framed the northern city as a hotbed of backward, violent, book-burning religious fanatics. On the other side of the world, but in a similar vein, Irfan Yusef in ‘Muslim Life in Sydney’ good-naturedly debunks the lazy Islamophobic stereotypes that abound, to reveal that Sydney’s Muslim population have the same diversity and drive exhibited by Dearborn’s Arab-Americans.

Nimra Khan’s vivid account of the heroic resilience of Lahore’s Third Sex community in the face of bigotry and hypocrisy, reminds one that although cities are harsh unforgiving places, common humanity will be found amongst the marginalised. We inevitably yearn for a simpler, less complex social organism. Robert Irwin, in his hugely evocative and entertaining essay on medieval Basra tempts us at every turn. Although ninth-century Basra was most likely a rough old place, who wouldn’t want to be transported back for a day, to walk through the Mirbad, where the Bedouin parked their camels and the lizard vendors displayed fat skinks (a local delicacy) for sale, before bumping into the famed goggle-eyed scholar and bibliophile al-Jahiz, on his way to be locked up in a bookshop for the night.

Detroiters are rightly proud that their city remains famed worldwide for its cultural innovation that has always been driven by the beat hammered out in the city’s car plants. In 1932 Mexican artist and revolutionary Diego Rivera, accompanied by his wife Frida Kahlo, was invited by art enthusiast Edsel Ford to Detroit. After spending time sketching in River Rouge and other factories Rivera produced Detroit Industry – the truly magnificent panoramic twenty-seven panel mural decorating all four walls of the courtyard of the Detroit Institute of Arts. You can only stand in awe, your vision sweeping across a combination of scenes of heroic workers toiling on production lines, depictions of the power of twentieth-century industrial invention, entwined with symbols and vistas from Mexican land-mythology.

Berry Gordy worked on the Ford assembly line (including a spell at the foundry at River Rouge) before going on to found Motown records (Motor-City Records). He modelled his hit-factory on Henry Ford’s original idea – artists in one end and perfectly crafted three-minute pop songs out the other: ‘Every day I watched how a bare metal frame, rolling down the line would come off the other end, a spanking brand new car. What a great idea! Maybe, I could do the same thing with my music. Create a place where a kid off the street could walk in one door, an unknown, go through a process, and come out another door, a star.’ He even set up a system at Motown called ‘quality control’ and famously filmed Martha Reeves and the Vandellas’ 1965 hit ‘Nowhere to Run’ on the Ford Mustang assembly line. Later on the 1970s thrash guitar band MC5 (the Motor City 5) served as a seminal influence on the punk rock explosion. MC5 fan, the idiosyncratic rock star Iggy Pop, who hails from the nearby Michigan city of Ann Arbor, claimed that he was inspired by ‘the industrialism in Detroit…what I heard walking around…boom boom bah – ten cars…boom boom bah – twenty cars.’

John Collins of Underground Resistance

Today the city’s mantle of industrial musical innovation rests with Detroit Techno. John Collins, a central figure in the movement, shows me around the headquarters of Underground Resistance – round the corner from the Motown Museum. A former auto-workers’ union hall, the building is part museum, part studio, part record distribution centre and global destination for techno aficionados. John has a real sense of history, he is endowed with a broad vision, and is a man very much worth listening to. He gives me a quick history of the musical form. It was founded by ‘the Bellville Three’ – three black high-school friends from a Detroit suburb, who, in the early 1980s, absorbed the diverse influences of the industrial/cultural life of Motor City in decline, the legacy of Motown and funk, sci-fi such as Star Trek, and electronic music coming from bands in Europe – most notably Kraftwerk whose most famous tune is, fittingly, called Autobahn. The result was a futuristic, soulful, electronic musical sound that also served (and serves) as a musical commentary on post-Fordist decline and social distress.

Collins is busy, but takes time out to educate me on the pioneers of Black Detroit, such as the city’s first African-American mayor Coleman A. Young, elected in 1974, much to the horror of the city’s white racist power structure. I’m certain that many people feel that the majority black population is today being punished by the powers-that-be for having the temerity to take political control of Detroit. Underground Resistance also has echoes of the legendary Underground Railroad – the hidden chain of sympathisers along which escaped slaves from the southern plantations made their way north to Detroit, and the final leg of their perilous journey, across the Detroit River to Windsor, Ontario, and freedom. John refuses to allow the present state of Detroit to obscure its history, its unique spirit and achievements. ‘A lot of good things have always gone on in this city.’ It will rise again. ‘Detroit is like an alcoholic. It has hit rock bottom many times. But it always picks itself off the floor’.

Later that evening, walking through the Eastern Market district, I pass by a bar. I stop to glance through the window. Inside mixed couples, black and white, are drinking and enjoying themselves after a hard day’s work. Some are squeezed onto the tiny dance-floor, dancing and singing along joyously. I can’t hear the music, but I fancy it is the urban blues number Joe L. Carter wrote while working the line at River Rouge in 1965:

Please, Mr. Foreman, slow down your assembly line.

I said, Lord, why don’t you slow down that assembly line?

No, I don’t mind workin’, but I do mind dyin’.

At this moment they look like they don’t have a care in the world.