Stay crouched on the earth,

come closer to our disintegrating bones.

You are so far away.

Countryside

‘I feel that everything I touch turns to sand.’

‘I’m very tired. I’m impatient with everyone, just want to be alone, go to the village and sleep and work in a garden and not be with anybody, not even my husband. I’m tired of stress, tired of everything.’

‘I feel worthless – sometimes I don’t want to live anymore.’

‘I think there will be another war.’

Many Bosnians are despondent and suffering from the late emergence of symptoms of trauma.

‘I am so angry. About the war. Yes, it’s finished almost twenty years, but my brother escape and now he lives in Australia, so how can I see him? I visited him last year, and it was wonderful to be with him and his family, but when it’s time for leaving, it was very hard. I cried, you know. And I still crying. Families are scattered in the world. All because of the war. I am so angry.’

During the Bosnian War of 1992–95, over 100,000 people were killed, and two million were displaced.

‘My marriage is broken. My trust is gone, and I feel so differently. I have a good job, but there’s bad atmosphere at work and our salaries go down each year.’

Divorces have soared and unemployment has been over 40 per cent for many years.

‘There’s one war criminal, convicted nearly twenty years ago, and he’s served many many years in prison. And now he being released, and those stupid people, they welcoming him! Like he’s a hero! Those people are very stupid, they don’t understand anything.’

War crimes are being tried not only in The Hague, but also in national and local courts. Many people complain about the lengthy delays of the trials and the low numbers of war criminals apprehended.

‘It was Europe’s fault. The war. I mean, Europe let it happen, and then waited over three years before it bombing and ending it. Three years!’

The Bosnian War ended after NATO bombed the Serbian positions besieging Sarajevo. Many Bosnians felt abandoned by the outside world and still feel resentment.

Bosnia is unhappy. I’ve not been there for five years and now that I’ve returned, I am rocked by its onslaught of despair, fatigue and pessimism. For Bosnians, the future seems to offer a fearsome spectre of poverty, unemployment, injustice, corruption, division and, for some, even a renewal of war. But mainly an intolerable continuation of the present, hopeless status quo.

This is bleeding into the personal lives of my friends, in the form of divorce, depression, suicidal impulses, and suspicious death. But fortunately the nightmare seems to spare some of the younger generation, who are marrying, starting families, and beginning to make their way as anything from teachers to tourist guides.

There has been much rebuilding, not all of it tasteful, and some of it rather puzzling – for instance, a huge modern shopping centre in Sarajevo containing luxury goods that hardly anyone can afford, and a rash of mosques although people say that existing mosques are not at all over-subscribed. But there are fewer abandoned ruins, and tourists now crowd the narrow streets, so the towns feel more normal, if one can ignore the common spattering of bullet holes in the walls.

For me the saving grace of this visit is the unfailing warmth of its people. My friends, acquaintances and former students welcome me with open arms and an immediate offer of deliciously strong Bosnian coffee. As we settle down to our conversations, they take me into their confidence and lay out for me the details of their lives, fears and dilemmas with touching bravery and honesty. And it does take courage to endure all this, on top of the ghastly memories of the war itself which, of course, still hang in the air. It’s been twenty years now, but it will take many more years before its effects start to fade.

I have my own personal disappointments. I was looking forward to hearing the wonderfully romantic folk-music of the region, called sevdah, but no-one can tell me of any bars or clubs where it is played anymore. And the famous bridge in Mostar is no longer white and pristine as it was when it was first rebuilt and unveiled in 2004. It has lost its sheen, and somehow this embodies my sense of Bosnia itself.

Despite all this, I have to admit that I’m very glad to be back. Yes, it’s incredibly stressful to see how my friends suffer, and to listen carefully to their distressing tales for hours on end. But the young people are grasping at enjoyment where they find it, and there is an intensity and rawness to life here that I know I will miss when I return to London next week. I’m lucky to be able to come and go, and I bless my lucky stars every day that I’m here.

Graves on the hillside

Speed is all, you said.

Sunlight hurts my eyes. I’m speeding now –

along its tracks the train is carrying me to.

We’ll go together, you said.

You said, it’s not so far, see,

just across the street,

two big breaths will do it. Ready?

Onetwothree, you said.

We ran.

Often. Every week.

Sniper Alley.

Onetwothree, you said.

We ran.

But you.

Grass and weeds grow over.

Sunlight hurts my eyes.

Speed is all, you said.

During the war, snipers positioned themselves in tall buildings and fired on civilians – men, women and children – as they ran to pick up water and food. The main street in Sarajevo became so dangerous that it was renamed ‘Sniper Alley’.

The new Stari Most

‘It’s not at all the same – it’s our bridge, but it’s not our bridge.’

The hill catapults fire

throughout the night. A choir

of missiles calls us from our beds,

from dreams of ordinary times

before they conjured crimes,

split our town, crazed our heads.

We run to broken windows.

Does the Bridge stand? Shadows

of stone flicker into the river.

Emptiness is hard

to see. The air is jarred

to flow so free. Oaks shiver.

Mostar’s iconic bridge, built by the Ottomans in 1566, was destroyed by days of shelling in November 1993. Its reconstruction was meticulously carried out by an international consortium, to the exact specifications of the original. When the new Stari Most was unveiled in 2004, its stone was a brilliant white, and it seemed to float and shimmer high above the green river. But now it has lost its sheen, its surface is already greying and stained, and it no longer seems capable of reflecting the light of the sun.

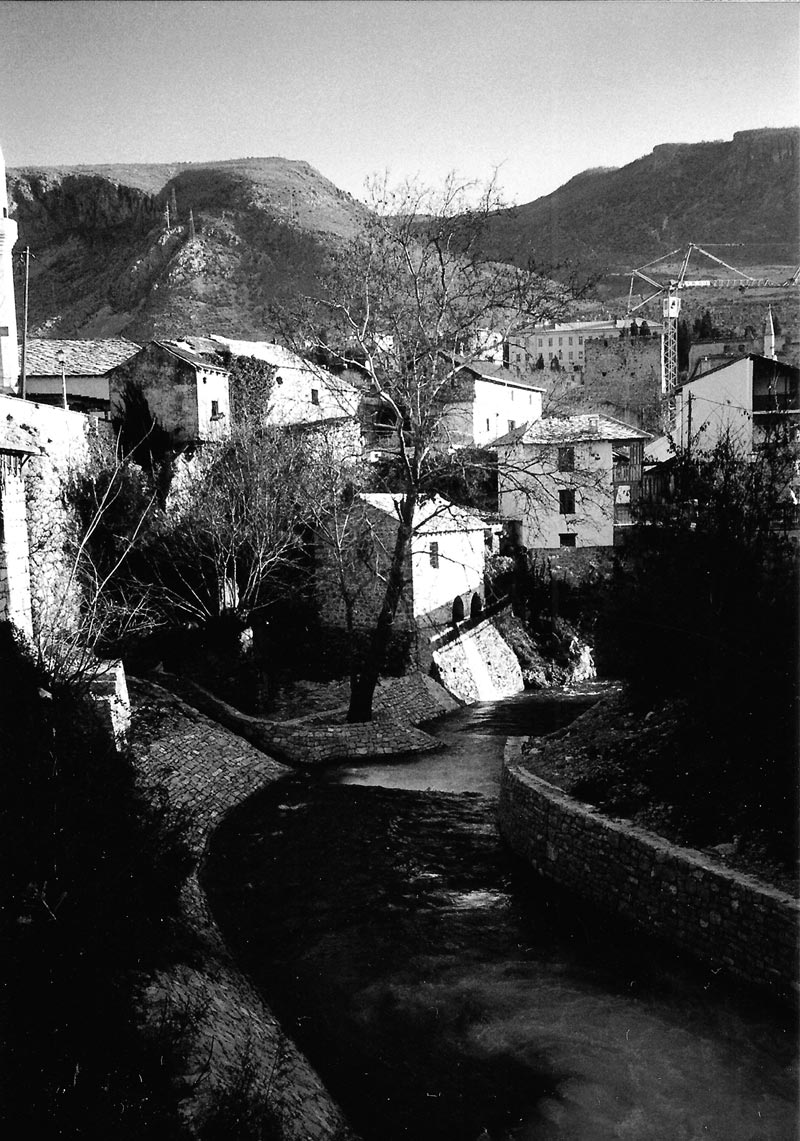

A small alleyway in Mostar

Playing music – not an option, while

outside my window, ‘that’ is going on.

My violin stays unbidden, mute, packed

inside its case, no glorious melting sounds

to soothe and make a pillow for my shattered

trust. What music keeps us true to our

burning, coruscating anguish? holds us

inconsolable? Music, choking,

falters into silence, while they fall,

dying, on the lane outside my window.

Mostar, the most destroyed city in Bosnia, lies in a beautiful valley, with its pretty houses rebuilt with its original light-coloured stone.

Darkness oozes from my pores,

blackens my thoughts,

fills my days with night.

Fault-lines in my skin slowly

widen, tear, split;

debris from those three mad years,

now fermented, ripe,

push towards the light.

I can no longer hold myself together.

Cover the sun, and I will sleep,

before my heart scatters like shrapnel in the field.

Old and new

After that, I didn’t go out.

Stayed inside my two dark rooms.

They brought me food, my friends.

I wasn’t going out. Ever. Never –

my body smothered in terror –

until this is over.

It won’t be over.

Every day a month.

Every minute a year.

I read my books, slowly.

Centuries pass.

And then, one morning,

I opened my door,

walked down the concrete stairs and out

into the autumn air.

They can’t make my home a prison. And

they can’t make me run. I’m not

going to run. Ever. Never.

So I walked, a crazy young woman, head held high.

I walked in my town and smiled at the sky. And

wherever I went, they held their fire.

They saw me coming, normal and easy, and

all of them held their fire.

To Be To Be. Shakespeare’s existential conundrum is altered to become a double affirmative. In Sarajevo, there is no question.

Maybe they are right.

Their thoughts, unspoken,

stare out of their eyes:

‘She has no right

to be sad’

because

there was

no bullet

no sniper

no grenade

no mortar

no explosion

no fire

no dying from starvation

only a car, an everyday car,

an everyday

car accident.

It shouldn’t be allowed in the middle of war –

accidents –

pitifully low in the hierarchy of deaths.

So I have to slaughter my grief

smother it

strangle it

starve it

push it deep where its pulse can’t be felt.

Mourning is postponed until further notice.

Today, and today, and today, I estrange myself from myself.

I make myself unnatural, a living ghost.

Until tomorrow.

Elaborate doorway. Sarajevo still bears signs of its cosmopolitan culture.

Sevdah! Sevdah! How I long for you!

A bride in white waits for her faithless groom,

and many a girl sighs as fruit is picked.

Sevdah! Sevdah! Where are your sweet tones?

Magicked on the bare karst mountain slopes,

flavoured with green valleys, stone-clad towns,

where are your plaintive harmonies? your swaying

rhythms? sad, accepting melodies?

Sevdah of my soul, of all our souls,

keep us in your embrace, together, whole,

sevdah, my love, we are too much divided.

Sevdah loosely means a longing of the soul, melancholic love. The lyrics are mainly romantic outpourings used in courtship. The performance of sevdah is becoming less frequent as popular music takes over.

Two doors in Sarajevo

Sometimes you have to forget.

Because forgiving is impossible.

And even if forgiving were possible,

You’d have to forget.

If you succeed in forgetting,

You won’t know what you should be forgiving.