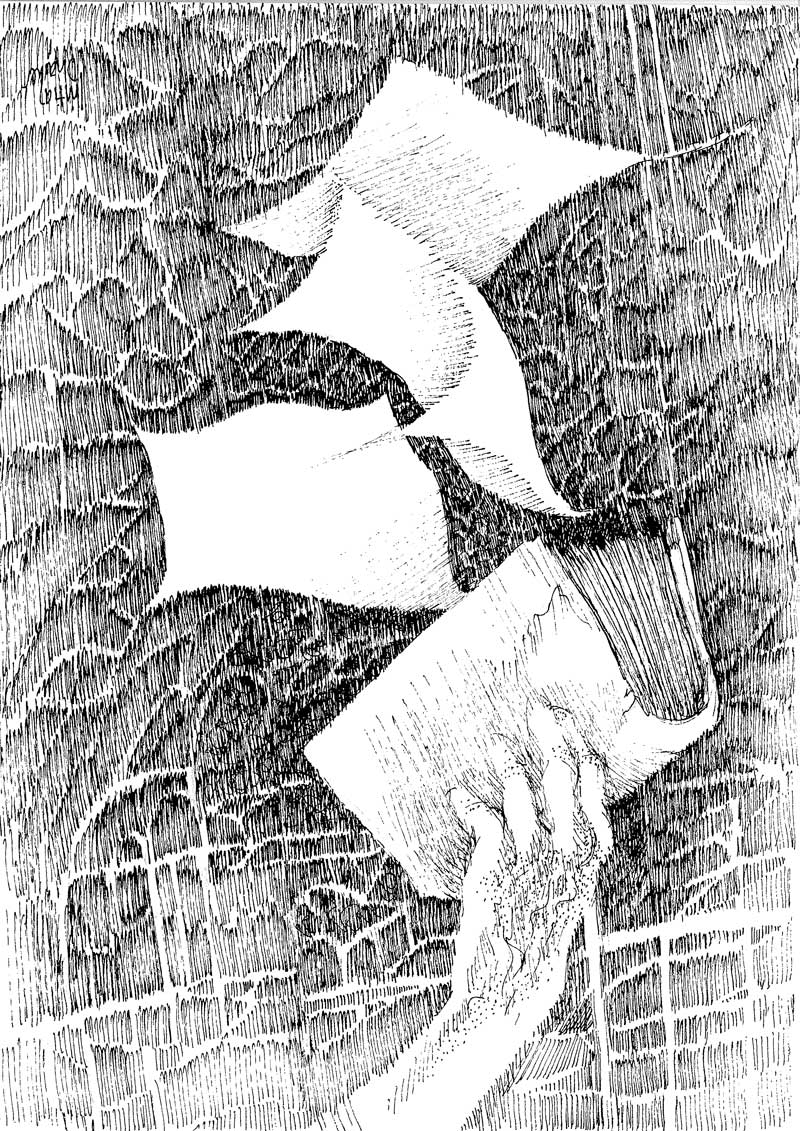

Whim

How did it begin?

Where did my whim start

its journey into this

monstrous, magical thing?

I think I travelled

not outward, but within,

and came back

dragging bits of wreckage

from my dreams:

the ragged cloud, the twisted tree,

a concept of eternity,

a man.

Strange,

to have thought up this thing

in its asymmetry,

no longer an abstraction,

quite complete

from collar-bone to rib to hip,

A length of arm, a fingertip.

What was I thinking of

when I made this?

Naming the Angels

Naming the Angels

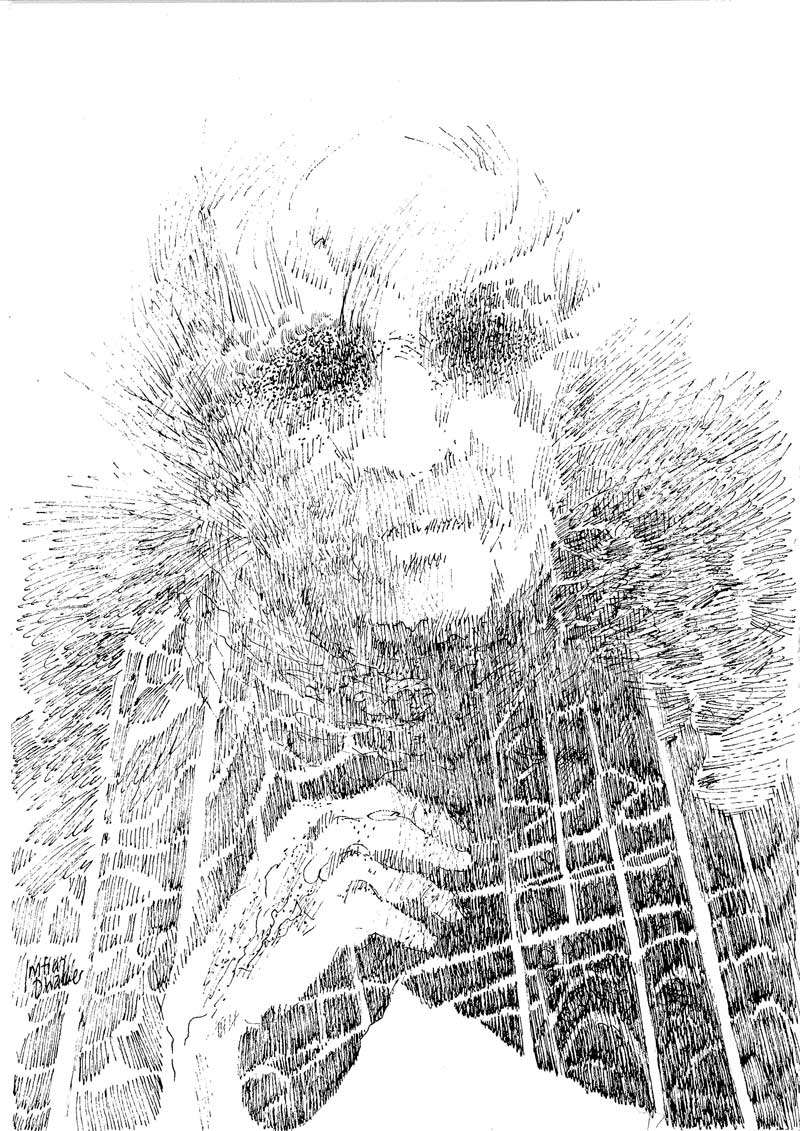

And Adam, when the names

of all the angels flowed

sweet as a prayer upon your tongue,

into a flurry, whisper-wing,

what skies split wide and glowed,

what bells were rung

ice-sharp upon the air?

A hush: each one held his breath

before the word enfolded him, strung

up, suspended there

like beads upon your voice;

and each one bowed,

perhaps to you, perhaps under the great

load of this new knowledge,

the real beginning of the road

from flight to fall.

All of them stung

into separateness.

Alone, within

the pride of being named –

the first sin.

Namesake

Adam, your namesake lives

in Dharavi, ten years old. He

has never faced the angels, survives

with pigs that root

outside the door,

gets up at four,

follows his mother to the hotel

where he helps her cut

the meat and vegetables, washes

it all well, watches

the cooking pots over the stove

and waits, his eyelids drooping,

while behind the wall she sells herself

as often as she can before

they have to hurry home.

He very rarely runs

shrieking with other rain-

splashed children

down the sky-paved lane.

He never turns to look at you.

He has no memory

of the Garden, paradise water

or the Tree.

But if he did, Adam, he

would not think to blame you

or even me

for the wrath that has been visited,

inexplicably, on him.

Reflected in sheets of water

at his back

stand the avenging angels

he will never see.

Adam from New Zealand

Adam from New Zealand

Adam is a journalist,

newly arrived in India

at twenty-six, eager to seek

and understand,

and to record it all first-hand.

So on his way into Bombay

he has decided he must see

the real India in Dharavi.

He wants a guided tour,

to be fitted in his schedule

between the film studio

and a visit to the Chor Bazaar.

He doesn’t understand

why I refuse to take him,

like all the others, lugging

cameras and microphones,

sunguns, recorders, dictaphones.

How can I serve up Zarina

or her brother Adam

to their random cameras?

They will smile shyly.

The aperture will open

to swallow up their souls.

Their mother will send out

for Thums Up, or

from the stall at the corner of the lane,

glasses of hot, sweet tea.

She will put on a brave face,

but everyone in Dharavi will know

the world has come with cameras

to make a side-show

of her poverty.

And will you come back,

in ten years’ time,

with your unidirectional mikes

and your portapacks

to make a record of Zarina’s wedding,

or a video of Adam’s bride?

Adam, your namesake lives in Dharavi.

But I will keep him out of reach

of your greedy camera.

He is too precious for you to see.

Guardians

Strange how the guardians

of our morals

have jellyfish mouths

and jamun eyes.

Funny how your fingers

slither into juicy things

where they don’t belong;

how the pot-belly

sits with your holy abstinence.

Odd how, in those frequent mirrors,

your haloes don’t show up,

and your media-buttered goodness

turns gargoyle.

Dealing with the devil

Arshad said his uncle from Bradford

switched off the TV set one day

right in front of the children’s faces

in the middle of Ice T,

dragged it out, smashed the screen

and carted the corpse away

to the dump,

leaving them sitting there,

the world cast out, all chatter exorcised,

Arif, Zubeida, open-mouthed Nasreen,

their faces left quite bare

as if they had been pulled off.

One devil had been dealt with.

You have to start somewhere,

Arshad’s uncle said.

6 December 1992

This morning I woke

and found my eyelids

turned to glass.

Through closed lids

I saw the whole world

changed to glass.

Glass door, glass lock,

glass gods in makeshift shrines.

When I blink,

glass eyelashes crack.

Outside,

blood runs in transparent veins,

fragile bodies walk the streets.

Through glass clothes

it is clear:

Some are circumcised, some not,

but circumcised or not,

they are all glass.

Glass leaders laugh

and the whole world can see

right through their faces

into their black tongues.

And through the crystal night

the bodies begin to burn.

The right word

Outside the door,

lurking in the shadows,

is a terrorist.

Is that the wrong description?

Outside that door,

taking shelter in the shadows,

is a freedom fighter.

I haven’t got this right.

Outside, waiting in the shadows,

is a hostile militant.

Are words no more

than waving, wavering flags?

Outside your door,

watchful in the shadows,

is a guerrilla warrior.

God help me.

Outside, defying every shadow,

stands a martyr.

I saw his face.

No words can help me now.

Just outside the door,

lost in shadows,

is a child who looks like mine.

One word for you.

Outside my door,

his hand too steady,

his eyes too hard

is a boy who looks like your son, too.

I open the door.

Come in, I say.

Come in and eat with us.

The child steps in

and carefully, at my door,

takes off his shoes.